One of my own maxims regarding lean implementations is that, if a company goes into a lean implementation with its primary goal that of cutting costs…it will fail. Sadly, too many managers and practitioners disagree. Essentially, they just don’t understand the economics of lean. They tend to look at the wrong end of the transaction between seller and buyer.

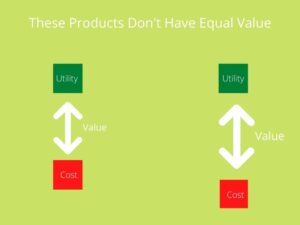

The wrong interpretation of lean economics leads us to believe that the best way to get customers is to reduce our own cost structure. That might be true if what we’re selling is a commodity that can’t be differentiated in the market. If we’re both selling a product or service that can’t be differentiated, then the customer will certainly buy from the one of us who has the lower price. Even in that narrow situation, we’re better off seeing the customer as striving to maximize his or her value. If the customer can’t discern which of our products provides the greater value, it’s rational to base the buying decision on price. The buyer’s decision looks like this:

Here’s the thing: If we’re differentiating our product on price alone, it’s easy for our competitors to follow suit and price their products below ours. Now we and our competitors are tied together in a race to the bottom that neither of us is likely to win given that we can’t reduce our costs or our prices to zero. But that’s what “lean as cost reduction” tries to do.

The better strategy, then, is to differentiate one’s own products and services in ways that it’s difficult for competitors to emulate. That’s exactly what lean does. Let me make this clear: lean doesn’t provide strategic advantage by allowing the manufacturer to lower costs. It provides strategic advantage by creating organizational capabilities that allow the manufacturer to provide increased utility to the customer.

I once facilitated a value stream mapping team at a steel making company here in Ohio. A team member asked me to provide a definition of lean. He said: “I’ve been to all sorts of seminars and heard all sorts of definitions but I still don’t think I understand what it’s all about.”

I responded, “I don’t have a concise definition but here’s how lean works: What’s the lead time that you quote when a prospective customer calls?”

“About twelve weeks,” replied the engineer.

“And I bet you hit that every time, right?”

The engineer chuckled, “It’s considered a success if we fulfill the order in sixteen weeks. We’ve taken as long as 36 weeks to fulfill an order.”

So, I asked, “If we could hit that twelve week mark consistently, would that help the company, even if we didn’t reduce our costs by a nickel.”

“Without question, our sales would increase.”

I went on: “So, let me ask this…if we could consistently hit an eight week turnaround time and still not take a nickel out of our costs, would that benefit us?”

The engineer’s quick reply: “We would control the market.”

The conversation illustrates, in a nutshell, the true economic value of lean: it differentiates the product and service on factors other than cost. Though our price is the same, perhaps even a bit higher, than that of our competitors, the customer sees more utility, therefore, more value in our product. In this case, the buyer’s decision looks like this:

Whence comes this superior value, even if the cost might be higher? The truly lean organization provides, to customers, what they want, how they want it, when they want it consistently. Customers don’t worry whether they’ll get their product on time (if at all), in the right quantity (if at all), or if it will meet their expectations and standards. This reliability differentiates the lean manufacturer from its competitors. Lean, then, is a top line strategy rather than a bottom line strategy.

“But,” you might reasonably ask, “doesn’t lean, in fact, reduce the manufacturers cost of goods by reducing waste in processes?” The answer, of course, is yes. We’ll address that in our next article.